What would you identify as the climax and completion of Jesus’ life and ministry? Surprisingly, this is not a trivial question. One of the key differences between John and the synoptic gospels is that, where the synoptics portray the crucifixion as a necessary but incomplete act on the way to the resurrection, John portrays it as the climax and completion of Jesus’ ministry in itself. In place of Jesus’ cry of despair (Matthew 27.46, Mark 15.34), John records a cry of triumph ‘It is finished!’ (John 19.30). The promise of ‘living water’ springing from the belly or side of the one who believed (John 7.38), best understood in reference to the Temple prophecy in Ezekiel 47, is fulfilled in the blood and water from Jesus’ side at his death (John 19.34). No wonder the true testimony of this leads to faith (John 19.35).

But most of the NT would point to the resurrection as the completion. Paul’s theological linking of Jesus’ death and resurrection to our movement into and out of the water of baptism (Romans 6.3–4) suggests that crucifixion and resurrection belong together, and this is evident all through the proclamation of what God has done. This Jesus, whom you crucified, God raised from the dead, Peter tells the Pentecost crowd in Acts 2, and we are witnesses of this. Paul, in Luke’s parallel depiction of his ministry, also talks of ‘Jesus and the resurrection (anastasis)’ (Acts 17.18), so much so that his hearers think that Anastasis is the female consort goddess to the male god Jesus. Paul’s summary of the gospel for the Corinthians is that ‘Christ died for our sins…was buried…and was raised on the third day’ (1 Cor 15.3–4).

Yet most of the New Testament actually sees a third movement as an essential part and completion of Jesus’ work: the Ascension. We might miss this because of our theological tradition, but we often miss it because of our failure to read carefully. In Peter’s Pentecost speech, the climax of what God has done in Jesus is not the resurrection, but Jesus being ‘exalted to the right hand of God’ (Acts 2.33). In support of this, he cites Ps 110, the most cited psalm in the NT (just pause to take that in…), with its imagery of ‘the Lord’ (messiah) taking his seat at the right hand of ‘the Lord’ (Yahweh, the God of Israel).

Yet most of the New Testament actually sees a third movement as an essential part and completion of Jesus’ work: the Ascension. We might miss this because of our theological tradition, but we often miss it because of our failure to read carefully. In Peter’s Pentecost speech, the climax of what God has done in Jesus is not the resurrection, but Jesus being ‘exalted to the right hand of God’ (Acts 2.33). In support of this, he cites Ps 110, the most cited psalm in the NT (just pause to take that in…), with its imagery of ‘the Lord’ (messiah) taking his seat at the right hand of ‘the Lord’ (Yahweh, the God of Israel).

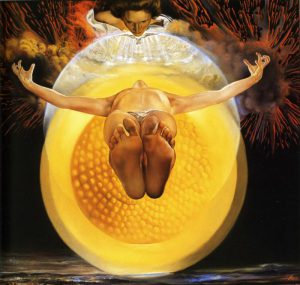

We can see how important this is, even in Paul’s theology. In his great hymn in Philippians 2 (I am not convinced Paul is citing a pre-existing composition), he actually skips over the resurrection and moves straight from Jesus’ ‘death on the cross’ to his being ‘exalted to the highest place’ (Phil 2.8–9). It is as if the movement from death to life to glory, in resurrection and ascension, are one movement—incidentally, a move that is mirrored in the language of the male child ‘who is to rule the nations with a rod of iron’ being snatched up to God and his throne in Rev 12.5. In John, Jesus makes reference to this by the garden tomb, telling Mary not to hold on to him because he has not yet ascended, and, most intriguingly, the gospel message she is given for the disciples is ‘I am ascending to the Father’ (John 20.17). Luke divides his work into two not on the basis of the resurrection but at the point of the Ascension:

In my former book, Theophilus, I wrote about all that Jesus began to do and to teach until the day he was taken up to heaven… (Acts 1.1–2)

So why do we miss the importance of this? It largely comes down to misunderstanding Daniel 7 and its appropriation in the New Testament.

In my vision at night I looked, and there before me was one like a son of man coming with the clouds of heaven. He approached the Ancient of Days and was led into his presence. He was given authority, glory and sovereign power; all nations and peoples of every language worshiped him. His dominion is an everlasting dominion that will not pass away, and his kingdom is one that will never be destroyed. (Daniel 7.13–14).

Although Jesus appropriates the language of ‘one like a son of man’ to refer to himself, in Daniel this is a corporate figure; just as the four beasts earlier in the chapter have been personifications of the four great empires (Babylonian, Persian, Greek and Roman), this human figure is a personification of God’s own people, currently oppressed and persecuted by the powers that be, but trusting God who will rescue them, bring them into his presence, vindicate them and give them power and authority over those who currently have power over them. A parallel to the visions in the first part of Daniel (the four beasts correspond to the four parts of the statue in Daniel 2), it represents the inversion of power that Mary describes in the Magnificat—’you have scattered the proud in the imagination of their hearts’ (Luke 1.51).

In taking up the title ‘Son of Man’, Jesus is claiming to fulfil the destiny of Israel—to take on their oppression, but also to experience the vindication from God. This also involves a crucial re-interpretation as well: it is not the empires of this world that are the true oppressors of Israel, but the powers of darkness and their own sin and disobedience. Thus when John the Baptist ‘goes before the Lord to prepare his way’ it is through ‘the forgiveness of all their sins’ (Luke 1.77).

But the key thing to notice in Daniel 7 is the phrase ‘coming with the clouds of heaven’. This is associated not with anyone’s coming from heaven to earth, but rather the opposite—the exultation of the Son of Man as he comes from the earth to the one seated on the heavenly throne. This is language both distinct from, and opposite to, Paul’s use of ‘coming on the clouds’ in 1 Thess 4.17. This would have been very obvious to Paul’s readers, since he uses quite different language for ‘coming’, the word parousia meaning ‘royal presence’.

But the key thing to notice in Daniel 7 is the phrase ‘coming with the clouds of heaven’. This is associated not with anyone’s coming from heaven to earth, but rather the opposite—the exultation of the Son of Man as he comes from the earth to the one seated on the heavenly throne. This is language both distinct from, and opposite to, Paul’s use of ‘coming on the clouds’ in 1 Thess 4.17. This would have been very obvious to Paul’s readers, since he uses quite different language for ‘coming’, the word parousia meaning ‘royal presence’.

Noticing this difference helps us unravel several key texts in the gospels. In Mark’s account of Jesus’ trial, Jesus says to the High Priest:

You will see the Son of Man sitting at the right hand of the Mighty One and coming on the clouds of heaven (Mark 14.62)

This cannot refer to Jesus’ return to earth (‘second coming’) unless Jesus was deluded about how soon that would happen. But more importantly, it cannot mean this because it is an almost exact quotation from Daniel 7, and refers to Jesus’ (the Son of Man’s) ascending to the throne of God and fulfilling the destiny of Israel. That is why the High Priest considered it blasphemy: in effect, Jesus was crucified because he anticipated his Ascension!

Similarly, Matt 24 makes no sense unless we read it in the light of Daniel 7. Jesus predicts that:

At that time the sign of the Son of Man will appear in the sky, and all the peoples of the earth will mourn. They will see the Son of Man coming on the clouds of heaven, with power and great glory… (Matt 24.30)

but then goes on to say, quite solemnly, ‘Truly I tell you, this generation will certainly not pass away until all these things have happened’ (Matt 24.34). Unless both Jesus and Matthew (and those collecting the canon) were mistaken, this must have already happened—and it did, in the Ascension. Jesus was caught up in the clouds of heaven to sit at the Father’s right hand in glory.

The lectionary reading for Ascension Day is Acts 1.1–11, the fullest account in the New Testament of the moment of Jesus’ ascension. There are a few important things to note about it.

We have already noticed that it is the Ascension which provides Luke with the point of division between ‘all that Jesus began to do and to teach’ and the continuing ministry of the apostles, through which Jesus continues to act and to teach by means of the Holy Spirit. What is striking in this account, though, is that Jesus’ teaching of the apostles ‘whom he had chosen’ can only happen ‘through the Holy Spirit’. Just as Jesus ministered by the Spirit (and after his testing in the desert ‘in the power of the Holy Spirit’, Luke 4.14), so after his resurrection he continues to do so, setting the pattern for the apostles themselves. They cannot continue his ministry until they, too, are ‘clothed with power from on high’ (Acts 1.8).

This is a time ‘after his suffering’ which appears already to be a semi-technical term for his being handed over, beaten, and crucified, his ‘passion’. You might think that his simply being alive was enough to answer any questions the disciples had—yet Luke agrees here with Matthew’s description that ‘some doubted’ (Matt 28.17) in that they need ‘many convincing proofs’.

The language of ‘forty days’ is significant throughout scripture. ‘Forty’ signifies an interim period of waiting, testing, and preparation, including the time the rain fell during the flood (Gen 7.4), the Exodus wanderings (Num 32.13), the periods of Moses’ life (according to Stephen in Acts 7, 23, 30, 36), Elijah at Mount Horeb (1 Kings 19.8), Jonah’s preaching to Nineveh (Jonah 3.4)—and so on. It is often the time period between major epochs in the biblical narrative of God’s acts of salvation.

Jesus continues to teach about the ‘kingdom of God’, which continues the central theme of his preaching in the gospels. This would make sense within a Jewish context, where God was thought of as ‘king’ and the eschatological hope was for the manifestation of his reign as king over Israel—and the whole world. But it is striking that as Acts unfolds, and within the writings of Paul that we have, the language of the kingdom takes second place to other language of resurrection and salvation.

The ‘gift which my Father promised’ echoes Johannine language from Jesus’ Farewell Discourse, which has been explored in recent lectionary readings. The contrast between the water baptism of John and the Spirit baptism of Jesus picks up the language of John himself from the beginning of Luke’s gospel (Luke 3.16), but this pairing also forms a theme in Acts, where those who believe are both baptised with water and with the Spirit.

The question in Acts 1.6 ‘Will you at this time restore the kingdom to Israel’ demonstrates the disciples’ continuing, nationalistic, misunderstanding of the meaning of the kingdom—so they really did need those 40 days of teaching! Rather than directly rebuke them, Jesus leads them in a different direction; the Spirit will equip them to be his witnesses ‘to the ends of the earth’. It transpires that this is the meaning of OT eschatological expectation that all nations will be drawn to Jerusalem, not in the physical sense of migration, but in the spiritual sense of being drawn to the Jewish messiah who was crucified and raise there. This becomes crucial at the Council in Acts 15 called to make sense of the ‘gentile mission’, and is reflected in Revelation’s vision of people drawn from every tribe, language, people and nation as the new multi-ethnic Israel of God in Rev 7.9.

Finally, the angel makes an explicit connection between the Ascension and the anticipation of Jesus’ return (never in the NT described as his ‘second coming’, paired with the incarnation, but as his ‘return’, pairing it with the Ascension). We might, on first reading, think that the correlation is being one of the means of travel, so to speak—he will ‘come back in the same way you have seen him go’. But the theological connection is much more significant. Jesus ascends to the throne of God, to sit ‘at his right hand’, exercising the power and authority of God by means of the Spirit. If Jesus is now Lord de jure then one day he must become Lord de facto. He final revelation as Lord of all is the inevitable consequence of his exaltation to the Father now.

If the Ascension is so important in the NT, what does it mean?

If the Ascension is so important in the NT, what does it mean?

- Authority. Jesus is enthroned with the Father. It is because of the Ascension that the lamb who was slain is seated with the one on the throne and shares his worship (Revelation 4). It is in the Ascension that ‘all authority has been given to me’ (Matt 28.18). And this authority means that Stephen is confident that he is held by a higher power, even to the point of death—his final vision is of Jesus ascended in Daniel 7 terms (Acts 7.55–56)

- Humanity. In the incarnation, God entered into human existence. In the Ascension, that humanity is taken up into the presence of God. We have a High Priest interceding for us who is not unable to sympathise with our challenges, dilemmas, suffering and weakness (Heb 4.15–16)

- Responsibility. The Ascension marked the end of Jesus’ earthly ministry; he has now given us responsibility to continue this work, empowered by the Holy Spirit. Jesus is not distant or indifferent, but he has delegated.

- Fidelity. Jesus ascending in the clouds to heaven promised that he will return ‘in the same way’ (Acts 1.11). His return is never called the ‘second coming’ in the NT, because it is not paired with his ‘first coming’ (the Incarnation) but with the Ascension. As God has put all things under his feet, one day his authority de jure will be an authority de facto.

(Published previously.)

I agree that the Ascension is important and under-rated. Without it, Jeus would not be able to intercede for us in heaven, nor could the Holy Spirit be sent and the church grow worldwide. But I disagree that the four animals in Daniel 7 are a recapitulation of the four parts of the statue in Daniel 2. They represent the four great empires that precede Christ’s Second Coming, just as the parts of the statue represent the four empires that preceded his first coming at the Incarnation. Daniel (7:17) was told that the four beasts were in the future, but the head of the statue represented Babylon which had already conquered the Jews, for Daniel was in the service of its king during the Exile. Of course there are parallels between the two sets of empires. It would also be weird for divine prophecy to use a different animal to symbolise Alexander’s empire in Daniel 7 and Daniel 8.

Let’s think about this. As Ian says ‘second coming’ is not a Biblical phrase. The first point to remember is that the Greek verb in the phrase “coming on the clouds” in Daniel 7:13 can mean ‘come’ or ‘go’. The direction of the movement needs to be discerned from the context.

[I noticed a similar problem some years ago when sharing an office with a Scot. Referring to a book he had at home he said “I will take it in tomorrow”, which I had to reinterpret it as “I will bring it in tomorrow.”]

In Acts, the two men in white robes tell the men of Galilee that Jesus will come (back) in the same way that he went (Acts 1:11). Therefore, there will be, ultimately, two “comings on the clouds”, one to heaven and one returning to the Earth. Daniel 7 has one like a Son of Man coming to the Ancient of Days. Therefore this “coming on clouds” must correspond to Jesus’ ascension.

At the Ascension He was going, not coming. But terminology isn’t relevant to my point, which is that the four empires in Daniel 7 are prior to His return in power to this earth whereas the four empires in Daniel 2 are prior to his ministry 2000 years ago. Why should Alexander’s empire be represented by different animals in Daniel 7 and Daniel 8? You can even recognise the lion with eagle’s wings and the bear.

I think to project back partially realised eschatology on to the text of Daniel is to do violence to the text, and ignores the fact that, until the ascension, no-one in Judaism—including Jesus’ disciples—envisaged a two-stage epiphany of God.

Daniel was told to seal up the scroll because it related to the times of the end, meaning it could not be understood properly before. It would be rash to assume that this meant only the last three chapters.

What would be the point of recapitulating the empires of Daniel 2 in Daniel 7?

What’s the point of Matthew repeating all those stories in Mark?

The fact we aren’t clear why is not a compelling argument about the text. Every mainstream commentator believes they correspond.

Yes, if you say that people who reckon they don’t correspond aren’t mainstream.

No, I don’t think I am being circular in this. There are very good reasons for seeing the two sequences in parallel.

They are in different literary forms, but the same language, and structural form the beginning and end of the Aramaic section at the centre of the book:

A. (2:4b-49) – A dream of four kingdoms replaced by a fifth

B. (3:1–30) – Daniel’s three friends in the fiery furnace

C. (4:1–37) – Daniel interprets a dream for Nebuchadnezzar

C’. (5:1–31) – Daniel interprets the handwriting on the wall for Belshazzar

B’. (6:1–28) – Daniel in the lions’ den

A’. (7:1–28) – A vision of four world kingdoms replaced by a fifth

What’s the point of Matthew repeating all those stories in Mark?

Assuming that Matthew had Mark’s gospel to hand (not vice-versa or a common ancestor) then the point is that Matthew regarded those things as just as important as Mark did, but Matthew wanted to write a self-contained account for a Jewish audience.

Were there distinct audiences for Daniel 2 and 7? And is it not odd that Alexander’s empire is represented by a different animal in the very next chapter? And is it mere coincidence that the two empires in our era that have had major dealings with the Jews are the British empire (symbol: a lion) and the Russian empire (symbol: a bear)? We all know who is the fourth empire in Daniel 7, but who is the leopard? We shall know soon enough…

The problems with this view:

(1) If the same word means both going and coming, that means that it can be going in Daniel and coming in Daniel’s reuse by a later writer. (The more general point is that original context may or may not be relevant in later use. In this case it is relevant since in each case the Saints of the Most High are due to inherit.)

(2) Why would an invisible going be such a major thing to look forward to?

(3) It must not be invisible anyway. This is the very event of which it is said ‘Every eye will see’.

(4) In that very same work, we have a Son of Man sitting on a cloud (ch 14), rather than approaching a throne swathed in clouds.

(5) That Son of Man’s trajectory is approaching earth.

(6) Revelation climaxes in the advent of Christ.

(7) Which indeed is the awaited event throughout the NT.

(8) And sometimes explanations like ‘going’/’coming’ are used to get out of a perceived hole, which clashes with the motive of reading the text as accurately as possible.

Problems with this view:

1. That would mean using Daniel to mean the opposite of what it means in context. There is no evidence that NT citations do this.

2. The ascension of Jesus is visible to the disciples, but also made visible all through Acts by his sovereign acts of power through the apostles.

3. In Acts 2, ‘all of Israel’ gathered in Jerusalem does indeed ‘see’ that God has made Jesus Lord.

4. You don’t have the exact image from Dan 7 anywhere in Revelation. So? Jesus sitting on ‘clouds’ indicates that he is in the presence of God (that is what clouds mean) and he exercises the judgement of God.

5. That Son of Man doesn’t move.

6. Yes it does—in chapters 19-22, not before.

7. And is waited for all through Revelation.

8. Au contraire, people use the idea to impose their own reading on the text, and making ‘coming with the clouds’ from Daniel mean the opposite when it fits their scheme!

1. -The main point of the discussion is that erchomai neither is nor can be its *own opposite. (All talk of opposites is relevant only to the English which is irrelevant to the original text.)

-Particularly once John has selected from the context (as every quotation must do) the apposite material, thus leaving out the remainder.

-The ‘going’/’coming’ thing is English, i.e. irrelevant to Greek (or Aramaic) texts.

-Moreover it is entirely dependent on one’s vantage point. Movement may be towards or away from earth, for example, but why prioritise that perspective?

-The Son of Man approaching the throne of God is moving in a more heavenly direction, but is *not moving especially further away from earth any more than he is moving nearer to earth.

2. When the acts of power happen, this is not centrally referred to in terms of ascension being made visible.

3. There are a lot of nations gathered, but it is hard to see this as the fulfilment of ‘every eye shall see him’; it is quite a good fit for the remorse and repentance. The ‘all of Israel’ could be grouped by Luke with ‘made Lord’ (primarily Joseph Christology rather than primarily low Christology).

4. The sitting is telling. John does not have to speak of sitting on a cloud, and it is surprising that he does so if Dan 7 is 100% his model. But he does. And that corresponds with the need of his readers for a deus ex machina with vehicle (explicitly understood as such by Matt 24) at this point in time. Which corresponds accurately to the particular words chosen from Dan 7 – this like every other quotation is selective.

5. Rev 14 multiplies characters beyond strict necessity for the author’s mathematical purposes. The ministry of that Son of Man does move towards earth.

6. Thoroughly agreed. But Rev 1 and Mark 13-14 and 1 Thess 4 etc are just as much an advent (particularly with the stress on visibility and on the vindication for which visibility is a sine qua non), and if a 2stage advent is never envisaged (whereas a 1stage is, e.g. at the start of Matt 24) then it could be a case of the law that any felt discrepancy can be immediately solved by multiplying entities.

7. Yes.

8. But some schemes are deduced, as schemes should always be. Those of whom you speak (and I agree they exist) have imposed a scheme rather than being data-led, so why pay attention to them?

-On ‘with’, ‘on’ and ‘in’: Distribution is: ‘With the clouds’ (Dan 7, Rev 1, Mark 14 – note that Mark is ‘with’ not ‘on’, not as said above – which supports your position; ‘on’ would certainly undermine it), ‘on’ (Rev 14, Matt 24); ‘in’ (1 Thess 4, Mark 13). The concepts within the clauses are identical but for the prepositions. So we are not dealing with opposites at all. We would be if the prepositions were opposites. But with/on/in are not each other’s opposites. Nor are they sufficiently distinct from one another to allow a great disjunction. And if a great disjunction between two different events were intended, (a) at least one writer would speak of both events in the appropriate terms, (b) they would not use over-similar language to do so, since that would be confusing.

Then there is the fourfold Lamb-Shepherd-Man-King found sequentially in Jesus’s four main appearances and identities in Rev and sequentially in GJn’s 4 behold sayings (of which the second is the followed Lamb, the Lamb who will be their Shepherd, familiar from Rev). This necessitates 4 different Rev epiphanies before we even start, but as you say it is only the last that is a decisive advent to impact earth. The 5th epiphany in ch1 stands outside the main revelation and duplicates one of the identities but allows John (the final available representative of the Twelve) to witness the Son of Man’s coming before his death as was expected and promulgated.

Delusion of Jesus? – This is presented as the only other alternative, yet is not even the most likely of the other alternatives. At the least this ch14 coming of the Son of Man must be the same as that referred to in ch13, which Mark knows is still to happen 38+ years on (33 to 71+) but schedules next in the cosmic agenda.

It could be that the NT writer picks out a phrase/clause from the context because that was the phrase/clause that did correspond to what he wanted to say, unlike its surrounds. Zech’s horsemen/chariots are varied by Rev. The four living creatures are varied from four faces. Etc.. There is a limit to how far the surrounds can be evoked, especially when OT is being laid on so thick as by Rev – there is barely enough space for echoes which crowd against each other, let alone for homage to *each of their contexts (Moyise over Beale here).

Love the photo of the feet from the chapel in the Walsingham shrine!

The Christological significance and beauty of the Ascension is an infrequently discussed topic within much Western theology, be it Protestant or Catholic.

If sin plunged human nature into the rampant invention of evil (Rom. 1: 29-30) BUT God has exalted human nature — in Jesus — to the “highest place” (Phil. 2:9), then there are innumerable implications to be drawn from Christ’s ascended and glorified humanity! This draws to mind Paul’s language of being seated “in (en) Christ” in the heavenly places (Eph. 2:6). If we are presently and mystically seated in Him, through His Spirit, then how does reality inform our present, daily process of transformation / sanctification?

If human nature is not only assumed, transformed, resurrected — but also glorified — in Jesus, then how does His glorification of humanity enable me to become a willing participant and ever-growing reflection of His divine nature (2 Pet. 1:4)?

Bulgakov, Solovyov and the preceding Slavophile theologians wrote extensively about this and titled it the doctrine of “Godmanhood” (bogochelovechestvo). Thank you for covering an often neglected Biblical truth with profound depth!

Kelly & Emmelia send their hellos and smiles to Maggie & you! Little Emmelia just mastered “dada,” “hi” and perusing through her picture books. I am a proud dad! 🙂

Grace & peace.

Thanks for that mixture of the profoundly theological with the personal!

If our participation in Christ means we too are seated in the heavenlies close to the Father so we cry out ‘Abba’ then Emmelia is being a great theologian in the Eastern tradition!

On a theological note: do the Slavophile put boundaries around the extent to which humanity is deified? How do we avoid an incipient pantheism, and maintain the creature/creator divide?

Generally, the Eastern Orthodox (including the Silver Age theologians) have a number of solutions to this:

Vladimir Lossky and the Neo-Patristic synthesis theologians, including the late Timothy Ware, stressed the essence-energies distinction of St. Gregory Palamas. Palamas worked to solve this dilemma by joining together a little bit of Aristotle and a “little bit” of St. Paul (Eph. 3:7; 4:16; Col. 1:29; 2:12) to create a stark divide between God’s “essence” (ousia) and God’s “energies” (energeia). According to the Palamite scheme, human beings can know, participate in, and reflect the activities and immanent revelation of God (ad extra) while always remaining precluded from participation in His essence (ad intra).

The Palamite approach creates problems, both Scriptural and theological (i.e. divine simplicity). Many Slavophiles worked to formulate an alternative to Palamism, including Solovyov’s and Bulgakov’s extravagant sophiological systems. Bulgakov did tend towards a universalistic eschatology; however, he was always clear that this ultimate reconciliation between God, humanity, and the world was panentheistic and not pantheistic. The deified human bears the image of the Son and is indwelt by the Holy Spirit; therefore, God becomes immediate to God through the creaturely medium of a deified human. However, the human does not become God.

“… This is the task and goal of creation. God created future ‘gods by grace’ for inclusion in the multihypostatic multiunity of the Holy Trinity and in the unity of the divine life… The difference pertaining to the hypostatic character of these theophanies remains, however, The Son becomes incarnate and humanized, while the Holy Spirit descends and makes His abode in men.” (Bulgakov, The Comforter, p. 356-357).

I hope that made some semblance of sense, haha.

Solovyov? His “Short tale of Antichrist” is utterly brilliant eschatological short novel/long story. He thought Catholicism was better than Orethodox theology, didn’t he?

I fully agree that the Ascension is underplayed by theologians. The short book (62pp) “Where is Jesus now and what is he doing: A fresh look at the Ascension” by David Pawson is excellent.

If the Ascension in Acts was Jesus taking the throne from a human pov. Is Revelation 4&5 His Reception from heaven’s pov?

The Ascension is indeed very important in the whole plan of Salvation for our benefit and blessing.

The death, resurrection and ascension of Jesus are all facts that the disciples scarcely understood {would we have fared any better?}

That, all, was accomplished by the power of God, it was not until they received power {of the Holy Spirit] did all become clear and confidently asserted thereafter.

Paul and the apostles were given illumination to the extent that the “born again” are regarded as united to/with Christ in every facet of this triune work of salvation.

Thus, we are/have been Crucified with and Raised, together with Christ.

The ascension of the saints is seen in Paul hammering out the nugget in his letter to the Ephesians as Ephesians 2:6 ;-

And HAS raised us up together, and made us sit together in heavenly places in Christ Jesus: and

CH1 v 3 Praise be to the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, who has blessed us in the heavenly realms with every spiritual blessing in Christ.i.e. “Daily loads us with benefits” as the Psalmist has it.

The triune salvation then becomes our Justification, Sanctification and Glorification, our place of REST.

As Jesus now *Sits*, “waiting for His enemies to be made His Footstool,” [the use of which would indicate a complete state of rest as it does for us in the natural.]

Jesus has made a way into the Holy of Holies i.e. into the place where God rests and gives Peace.

Rather than analyzing the Jesus of History, maybe we need a new

Jodocus van Lodenstein to reform the reformation?

A midst the theological, philosophical and ethical storms and the overwhelming white noise of our daily lives; Perhaps our best course might be to bunk down alongside Jesus in the storm and just rest.

Interesting thoughts. I think, on reflection, I would still answer “the resurrection” if asked what was the most important event in the New Testament (though with the caveat that none of the events can really be separated from each other).

It’s the resurrection that is new and truly unexpected, and therefore the point around which everything changes. But the ascension invests it with meaning. The resurrection of Jesus isn’t like Lazarus – he’s not restored to life to die again later, so he has to ascend. That’s not the only difference (Jesus’s resurrection has some strange things going on – the appearance in the locked room, not being recognised on the road to Emmaus, Thomas putting his hands in the wounds etc.) but it’s the vitally important one.

If we had Jesus death, and the ascension without resurrection, then what’s happened? A good man dies and is taken into heaven by God. The Gospel becomes: be nice, and do good things, and God will look after you when you die. If we had Jesus death, and resurrection but with no ascension, then what’s happened? Jesus has like Lazarus, come back to die again later, and his death becomes a neat trick at the expense of the Romans but nothing more. Or Jesus comes back, but ends up wandering off (into the wilderness again?), essentially abandoning us and becoming irrelevant.

The ascension is necessary to underscore what the consequences of the resurrection are for us: that life everlasting with God is open to us.

AJ Bell – yes, I agree with this. When Aberdeen beat Real Madrid in Gothenburg in 1983 to win the European Cup Winner’s Cup, yes – indeed it was necessary for them to return to Aberdeen in glory to display the cup in an open topped bus parade. But I’m sure that everybody would agree that the important part of the job was carried out on the football field in Gothenburg – just as with Jesus, the key part of the business was the victory over sin and death in the crucifixion and resurrection. The ascension to heaven to be seated in glory was simply the toffee at the end of the job.

Ah, wonderful thread. thanks for your insights guys.

The spirit of van Lodenstein lives on.

I dont like saying one event was the most important. To me you cant really divorce the death, resurrection and ascension of Jesus. And in Paul, for example, he emphasizes the cross and resurrection.

The ascension reflects Jesus returning to whence He came, but now changed after His sacrifice. And one could argue if He didnt return and take His throne again, He could not have sent the Spirit.

Has “Christ has died, Christ has risen, Christ will come again” contributed to ascension neglect? Can’t think, either, of too many recent theologies on the Ascension.

I’ve found Wesley’s “Arise, my soul, arise” to be a great help in worshipping the ascended one.